By George Bollenbacher

Ever since the US Alternative Reference Rates Committee (the ARRC) first announced that it had selected the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) as a replacement for the US Dollar London Interbank Offered Rate ($LIBOR), people have been focused on two significant disconnects between LIBOR and SOFR (and some of SOFR’s cousins in other currencies) – the fact that various LIBORs are quoted for many tenors, up to one year, while all the replacements are all overnight rates, and the fact that all the LIBORs contain a bank risk component while SOFR and SARON do not.

A Little History

In order to understand this disconnect and the attempts to deal with it, we first have to cover some history. Libor began in London in the 1960s as an attempt by the money markets to get out from under the iron hand of the Bank of England (BoE), which controlled what was then the largest short-term lending market in the world. The big banks in London began lending and borrowing directly between themselves without going through the BoE, and the volumes in that market grew substantially over the years.

Because LIBOR was based at the time on a liquid and growing market, the use of the rate also grew, in many ways. First it spread to many types of instruments, including securities, commercial loans, retail products like mortgages and auto loans, and various derivative instruments like swaps and futures. Second, it was quoted in a range of tenors, or terms, from overnight to one year. Third, it spread beyond London and the sterling market into almost every significant money center. By the 1990s LIBOR and its cousins (collectively known as the IBORs) were deep into the genetics of every financial market in the world.

But there was a significant problem with all this growth. By the end of the twentieth century interbank lending in London, as well as in most financial markets, had begun to dry up, as banks found more efficient ways to fund themselves and to invest short-term cash. One of the major vehicles was repurchase agreements (or repos), where a short-term lender simultaneously purchases securities from a short-term borrower and agrees to sell them back for settlement at some point in the near future.

With the growth of the repo market, by the early 2000s there was virtually no interbank lending going on, so the British Bankers Association, which collected the LIBOR quotes daily, was reduced to asking banks every day where they could borrow for the various tenors if they needed to, and that persisted when ICE Benchmark Administration (IBA) took over the index in 2014. Without a liquid market and actual trades to refer to, the temptation to fudge the LIBOR quotes became too enticing, and there were several major instances of rate manipulation, especially during and right after the Great Financial Crisis, or GFC. Those manipulations, which resulted in large fines and even prison terms, convinced the global financial regulators to find replacements for the various IBORs around the world.

Finding a Replacement

Once the decision was made to try and do away with the IBORs (and from now on I will focus mostly on $LIBOR) the working groups had to come up with a replacement that wouldn’t be subject to the same vicissitudes as $LIBOR, and that turned out to be a very difficult assignment. There were really two main requirements: there had to be enough daily trading volume in the underlying instruments to make manipulation impossible, and the rate could not be subject to the credit quality of the banking industry as a whole.

In the US, at least, those requirements shifted the ARRC’s attention to the repo market, which is both huge and generally assumed to be risk-free. There was, however, one big problem – virtually all of the repos done in the US are for very short term, generally under one week with a majority maturing overnight. Given the large trading volume in repos, and the reporting of that volume by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (the NY Fed), the ARRC made the decision to adopt SOFR as the officially blessed (but not officially required) replacement for $LIBOR. Then the hard work started.

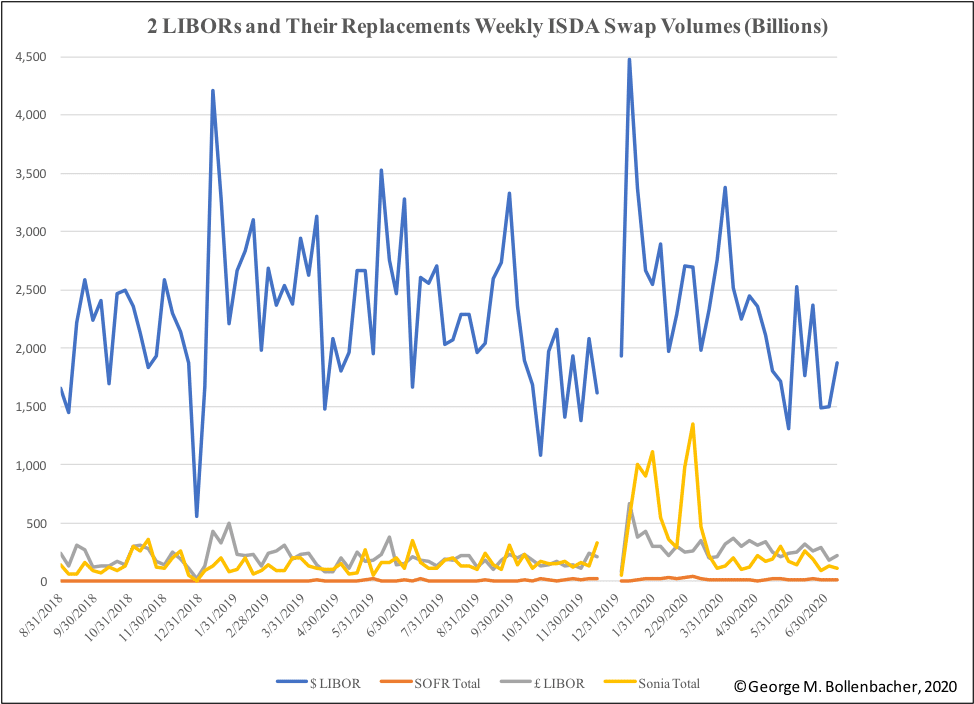

Once a replacement rate had been blessed, it wasn’t automatic that it would be used in all the many places where $LIBOR functions. There were many reasons – among them finding and fixing the multitude of systems programmed to access and utilize $LIBOR – but by far the biggest impediment was the single overnight tenor of SOFR. More than anything else, this impeded the acceptance of SOFR. How big a deal is that? Figure 1 shows weekly interest rate swap creation for four rates: $LIBOR, SOFR, £LIBOR and SONIA (the UKs replacement rate) since August, 2018.

Figure 1: Weekly New Interest Rate Swap Volume for Four Rates

Source: International Swaps and Derivatives Association

This chart shows that, while £LIBOR and SONIA are running pretty much neck and neck, an average of more than $2 trillion new $LIBOR swaps are being created each week (more than $2.3 trillion per week in 2020), while an average of $18 billion of new SOFR swaps have been created. The ARRC and other official bodies have been urging people to transition from $LIBOR to SOFR throughout this period, and have predicted that this transition would gradually build momentum, but it simply hasn’t happened in one of the biggest rates markets in the world.

Finding a Solution

Early on the ARRC recognised the tenor problem with SOFR. In March of 2018 they issued a press release mentioning “the creation of a forward looking term rate based on SOFR derivatives markets.” However, that effort soon died out, partly because the repo markets, and thus SOFR, were quite volatile throughout 2019, with regular spikes at month-ends. This was a particular concern because many rate resets that utilize the IBORs happen at month-ends.

This prompted the ARRC and others to change from the heretofore standard practice of setting the rate at the start of the period in question (and collecting the interest at the end) to setting the rate at the end of the period (defined as in arrears) based on the average of the overnight rates during the period and collecting almost immediately. However, this solution had very significant problems of its own. A simple example will make that clear.

Suppose we start a three-month rate period at an overnight (O/N) rate of 2%, and that there are 60 business days in that quarter. Further, let us suppose that the O/N rate rises by 1 basis point (BP) per business day throughout the quarter. At the end of the quarter, the forward O/N rate is 2.6%, but the in-arrears average rate is 2.3%. This creates a significant problem for someone trying to hedge a three month forward rate on a note by using the swaps market, and it’s worse if the rate shifts near the end of the quarter. If every short-term market switched to the averaged in-arrears methodology, this problem would appear to be solved, but that in itself raises a host of questions. As it turns out, the repo market stabilized somewhat after March of 2020, so averaging may now be a solution in search of a problem.

At the same time, the ARRC attempted to solve the problem of a lack of a term SOFR by suggesting that O/N rates be compounded daily through the rate term, which only works, of course, if we are using the in-arrears average. But this, too, appears to be an illusory solution. Using the standard formula of Rc= P (1 + r/n)nt, where Rc is the compound rate, P is the initial principal balance, r is the simple interest rate, n is the number of times interest is compounded per time period and t is the number of time periods, compounding 2% daily for six months generates a compound rate of 2.01%, In other words, it adds 1 BP to the simple rate. That works if the O/N-to-six-month yield curve is essentially flat, but in a flat yield curve we don’t need the compounding to set longer rates anyway. Under a positive yield curve, and especially in a market where the curve is shifting, the compounding solution doesn’t solve anything.

The ARRC has also issued consultations on many of these possibilities. In November of 2019 it announced a consultation on “Proposed Publication of SOFR Averages and a SOFR Index,” which asked:

- Is the proposed calculation methodology, including the compounding approach, appropriate for calculating the averages and index?

- Are the proposed fixed 30-, 90-, and 180-day tenors for the SOFR averages appropriate, or should the published averages follow a modified following convention (which would not result in a fixed 30-, 90-, or 180-day count) or some other convention? Does the SOFR index appropriately address the need for calculating flexible period averages?

- In addition to the proposed tenors for the SOFR averages, are there any additional tenors that should be considered for publication? Please explain the purposes that such tenors might be used for.

- Are there any changes to the proposed decimal precision for the SOFR averages or index that should be considered?

- Are there any other changes to the averages or index as proposed that would make them more useful? For what purpose(s)?

- Are the proposed publication arrangements, including publication dates and times, appropriate to facilitate use of the averages and the index?

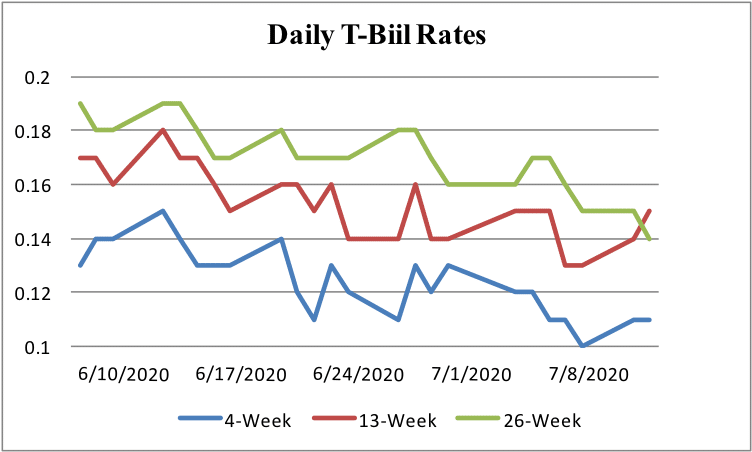

In February the ARRC announced the “Publication of SOFR Averages and a SOFR Index,” and said, “The large majority agreed with the proposed compounding methodology and publication arrangements of the SOFR Averages and Index…[so] the New York Fed judges it prudent to begin publishing the 30-, 90-, and 180-day SOFR Averages on March 2.” The reported average rates are the simple averages over the three reporting periods: 30-day, 90-day, and 180-day. I compared those rates to an available set of market rates, the daily Treasury Bill Rates published by the US Treasury. First let’s look at the T-Bill interest rates (not the discount rates) in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Daily Reported T-Bill Interest Rates

Source: US Treasury

We can see that, although the rates look volatile, each horizontal line represents 2 BP, so they are actually quite stable. For most of the observation period there is a very slight positive curve, but it is essentially flat.

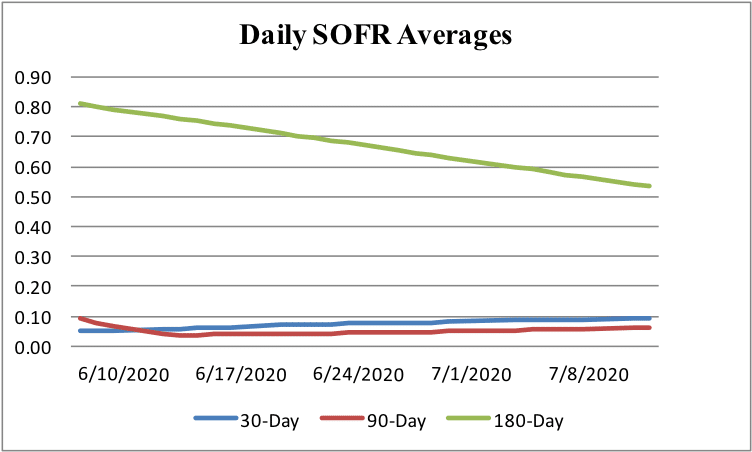

Now let’s look at the SOFR averages for the same period, in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Daily Reported SOFR Average Rates

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Here the 180-day line looks completely wrong, and it points out one of the implications of the SOFR averaging approach. Short term interest rates were in the 1%-1.5% range at the beginning of 2020, but dropped sharply to almost 0% in March. Because the 180-day SOFR is a moving 180-day average, it still reflects a significant number of observations at those higher rates. For sure it is falling, and will eventually get down to a level reflecting the current market, but meanwhile it’s a very flawed hedging and rate-setting tool. In the same way the 90-day average has caught up with current levels, but it shows a slightly inverted curve as opposed to the positive curve in Bills.

What this boils down to is that even this short testing period has pointed out a significant flaw in the current term SOFR approach. It’s a mathematical tautology that the longer SOFR term averages will be much less volatile than actual forward looking rates, which are the market-dictated benchmarks that SOFR should look to replicate. During periods of very low volatility, which is where we are now, this problem may look manageable, but it will rear its ugly head with a vengeance once rate volatility returns. Anyone expecting to hedge a forward-looking six-month borrowing rate with a 180-day SOFR rate swap will be in for a rude awakening whenever we emerge from the current pandemic conditions.

Dealing with Credit Risk

Finally, we need to look at the implications of having a bank credit risk component in the IBORs that is conspicuously absent from SOFR. The fact that all the IBORs fluctuate somewhat with the credit quality of a group of lenders (even if the risk-free rate (RFR) remains the same) was not widely appreciated by borrowers in general, but it was very clear to the major banks of the world. Having a built-in income buffer whenever the public perception of bank credit quality dips has come to be the sine qua non for bank lending, so the adoption of a repo-based replacement rate emerged as a cause of concern in banking circles. The issue was exacerbated by the understanding that in times of financial crisis (which we may be heading into under a resurgent Covid-19) the reference rate could dip as lenders flock to quality, while the banks’ borrowing costs would probably rise, which made their concern all the more urgent.

The real issue here is that the general bank credit risk component of the various IBORs is implied, not specified. One can derive it from comparing any IBOR to its RFR for the same tenor. Except, of course, that we don’t currently appear to have forward-looking RFRs for any tenors except overnight. As a result, the ARRC proposed a “Spread Adjustment Methodology…based on a historical median over a five-year lookback period calculating the difference between USD LIBOR and SOFR.”

In other words, market participants who adopted this methodology in 2020 would be agreeing to a rate of SOFR plus the median spread between O/N $LIBOR and SOFR since 2015. At every rate reset the formula would access SOFR (from the NY Fed) and the current median spread, presumably from an agreed-upon source like Bloomberg. However, this really means that the spread will very likely become static, since the whole purpose of all this effort is the eventual disappearance of all the IBORs. So, whatever the SOFR-to-$LIBOR spread is when $LIBOR is officially decommissioned will be the permanent spread, which doesn’t really solve any identified problem, and only serves to permanently elevate that adjusted rate.

Are There Any Tenor Solutions?

At this point it looks as if we have at least one significant problem and no surefire solutions. It is quite clear from the volume of outstanding and new $LIBOR derivatives, and the slow uptake of SOFR in the derivatives space at least, that we need workable and reliable risk-free term rates in the US, or the market will not migrate away from LIBOR. Various regulators and working groups have espoused a set of solutions involving SOFR futures and compounding, but the continued very low volume of new SOFR swaps tells us that it isn’t working, and it appears that no amount of cajoling by the authorities will change that. In fact, some participants are starting to contemplate the possibility that the regulators will throw in the towel in late 2021 and agree to let the IBORs, and $LIBOR in particular, limp along in its suspect condition.

Which raises the question – if the lack of a term SOFR is the crux of the problem, and the market recognizes that compounding and averaging don’t generate the proper reflection of a forward-looking term rate, is there any instrument with enough volume and the proper credit profile out there that can fill in?

In the US, at least, that requirement is fulfilled by two sources: 1) the regularly auctioned Treasury Bills, which are sold weekly in 13-week and 26-week maturities, and monthly in 52-week maturities and reported by the US Treasury , and 2) the Daily Treasury Yield Curve, also published by the US Treasury. Both of these benchmarks are reported by a governmental body, not a commercial enterprise, and are supported by very high trading volumes, which makes them very hard to manipulate.

Some might argue that we don’t want to base such a huge and important market on securities issued by a single entity, even if that entity is the largest debt issuer in the world, with the most liquid market for its securities. But lots of other markets and economies use national debt issues and their rates as a benchmark with far fewer problems than $LIBOR has had. In the end, and the end is fast approaching, the market will have to decide whether adjusting course in this way is smarter, or should we keep barreling toward that brick wall in the certain knowledge that it will crumble in time?